Hiring a new CEO/Executive Director is a pivotal point for any nonprofit organization. It is both an exciting opportunity to strengthen your organization’s future – and a potentially daunting and time-consuming undertaking. Here, I draw on my executive recruiter experience to share some don’ts and dos to increase your chances of success in hiring an exceptional new leader. These are guidelines which I believe prove useful during the majority of leadership searches…

5 Don’ts and Dos for Recruiting a New Nonproft CEO/Executive Director

5 Don’ts and Dos for Recruiting a New Nonproft CEO/Executive Director

Co-Founder

Posted March 21, 2022

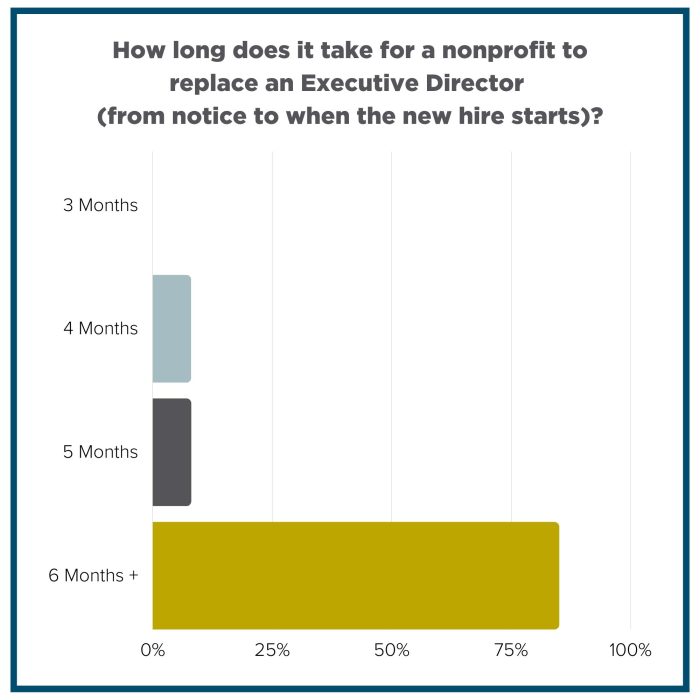

Don’t assume your new leader will begin work within 3-4 months of your current leader announcing their departure.

Don’t assume your new leader will begin work within 3-4 months of your current leader announcing their departure.

Four months would be nice but should not be expected. Hiring a new leader is just about the most important decision a board will make. That decision takes time – time to assess opportunities, assemble an ad hoc search committee, find candidates, make a decision, negotiate with finalists, and make an offer.

To test out my hypothesis, I recently conducted a LinkedIn poll that garnered over 100 votes. Here are the results:

Keep in mind, too, that a majority of the candidates will already be working in executive positions where giving notice and leaving in, let’s say a month, would be downright irresponsible. So, 4-7 months is the time to expect from the time notice is given to the time the new leader begins (please note, this is true even when the search itself takes only 3-4 months).

Do secure an interim with full authority to keep “the trains running on time” ASAP.

Do secure an interim with full authority to keep “the trains running on time” ASAP.

Select an internal staff member or retain a service to assign an interim leader as soon as you can. In any case, be clear whether or not the interim could be a candidate for the full-time position (I have seen interims succeed as the new hire—and I have seen it blow up).

Don’t grant staff voting rights on the search committee.

Don’t grant staff voting rights on the search committee.

Let me start by saying that I know that CEO/Executive Director search committees can be successful with staff as formal members. But I think that the risks far outweigh the benefits. Let’s start with the squirmy idea of staff hiring their own boss. More importantly, having staff on the search committee dampens the ability of the board to have candid assessment discussions. For example, what if the board wants to, or should, create a strategy for the new leader to eliminate the jobs function of select staff on the committee?

(Note: it is often helpful to have an outside non-board member(s) on the committee because of their special expertise or diverse experience but try to keep the total committee number small. I find that when there are more than nine committee members, there is less accountability. Find more advice on how to assemble a strong search committee in my colleague Tracy Marshall’s article: “How to Form and Manage an Effective Search Committee.”)

Do invite your head of HR to all meetings as a non-voting member.

Do invite your head of HR to all meetings as a non-voting member.

Your HR director should be present as it is their responsibility to manage communications with candidates, ensure confidentiality, craft the offer letter, etc.

Don’t assume your key staff will stay.

Don’t assume your key staff will stay.

A job insecurity sound alarm goes off for staff when they learn that the head of the organization has announced they are leaving. Staff might wonder: Will the organization go in a new direction? Will I get along with the new leader? Will they bring in their own team and sweep us out? Additionally, if staff were already aware that their leader was leaving, they may have begun to update their resumes and LinkedIn profiles, beginning their own search process.

Do identify your key players and involve them in the recruitment process.

Do identify your key players and involve them in the recruitment process.

To help retain staff, put their minds at ease, and ensure the new leader will receive a warm welcome, bring key players into the fold. While earlier in this article I advised against having staff join the search committee, I do believe that they can make important contributions throughout the search process. Staff members can play a role in everything from reviewing the job description to recommending candidates to interviewing finalists.

Don’t assume board members are fully aware of or in agreement about how to conduct the search.

Don’t assume board members are fully aware of or in agreement about how to conduct the search.

So, let’s begin by recognizing that the search committee is an ad hoc group, with untested assumptions, biases, and preferences, that needs to be in alignment around important decisions. In this context, there is real value for board members to draw upon their diverse nonprofit experience as well as other relevant professional and volunteer experience. But, it’s not safe to assume they are all on the same page concerning the job description of the new leader, their roles, or the decision-making process!

Here are some of the disconnects you might anticipate when a committee has failed to name and align expectations at the start of the search:

- One committee member could assume that the committee would only recommend one final candidate to the board, whereas the rest of the committee thinks they are recommending three.

- Several committee members could assume that when discussing diversity, it was limited to ethnicity, whereas other members may be referencing gender, race and/or age diversity as well.

- The chairperson might see their role as being primarily process facilitation with no special influence, whereas the rest of the committee believes the chairperson should have authority to make decisions when there isn’t a consensus among members.

- Academics on an arts board might publicize the finalist names on social media (which is common in higher education), while the rest of the committee would shudder at this violation of confidentiality.

- An untrained volunteer could be surprised to discover that they cannot ask candidates about their marital status or current salary.

Do address hidden assumptions at the beginning and throughout.

Do address hidden assumptions at the beginning and throughout.

Thankfully, there are ways to avoid these false assumptions. This is what works for me as an executive recruiter: At the beginning of the search, I spell out in writing what I believe are the committee roles and responsibilities. Then, committee members get a chance to weigh in, through one-on-one meetings and group discussions. This prompts revisions – and eventually leads to alignment.

(When addressing issues where the stakes are high, opinions are varying, and emotions are involved, I find the following book very helpful: Crucial Conversations by Joseph Grenny and Kerry Patterson.)

Don’t create a new comprehensive strategic plan before starting the search.

Don’t create a new comprehensive strategic plan before starting the search.

Great strategic plans articulate a compelling vision of mission, long term goals, and an effective plan for how to get there. They require a team to gather and analyze data, consider alternative scenarios, engage stakeholders, hammer out implementation budgets/calendars, and obtain formal board endorsement. It can take hundreds of staff and volunteer hours over the course of 3-4 months. This is too great of an undertaking to consider when a new leader needs to be hired.

Do consider Strategic Planning Lite.

Do consider Strategic Planning Lite.

What do I mean by this? Your committee can spend time identifying your organization’s values and goals without incorporating data, tested budgets, or timelines, etc. At the same time, this “strategic planning lite” could be a helpful reference point in assessing and recruiting candidates and in managing board, staff, and constituent expectations.

And most importantly, a new CEO/Executive Director will much prefer to lead their own comprehensive strategic plan. But you can give them a running start…

• • •

Hiring a new Executive Director/CEO is a significant and unique process – and I’m just scratching the surface with these 5 don’ts and dos. If you have suggestions for more don’ts and dos or have other questions or feedback, then please reach out to me at wweber@developmentguild.com.