Women now make up more than half of the American population. And according to the U.S. Internal Revenue Service, 47% of the country’s top wealth holders (defined by those who have assets of $2 million or more), across all generations, are women. These female top wealth holders have combined assets of nearly $5 trillion. It’s not surprising, therefore, that in recent years there has been more discussion, and more attention paid, to the women in philanthropy than ever before.

A Shift in Narrative

When we talk about women in philanthropy right now, the name that most people think of is MacKenzie Scott. Scott, has made staggering multi-billion-dollar gifts to organizations ranging from local chapters of Planned Parenthood to historically underfunded Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU). Her giving strategy has been both targeted yet private, and has been considered untraditional, without the large staff of private foundations of comparable means and the absence of a detailed explanation on her giving strategy. It’s undeniable that Scott’s gifts, many of which were made at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic when need was arguably the greatest, have marked a turning point on the philanthropic world stage.

It is easy to want to connect other major gifts from women philanthropists, such as the campaign to raise over $55 million to fund a new Smithsonian Museum to Women’s History, with leading gifts from Walmart heiress Alice L. Walton and fashion designer Tory Burch, to Scott’s trailblazing philanthropic leadership. But is this fair? Are these consequential gifts starting a ripple effect, or are they shining a light on a facet of philanthropy that has always existed?

How Women Give

Studies conducted by the Lilly Family School of Philanthropy at Indiana University have consistently found that households led by women, regardless of the total household income, give more money to charitable organizations than men with comparable income levels. This contrast is most dramatic in women of the Baby Boomer generation, whose incomes propel them into the top 25% of the country’s wealth holders. Overall, women across generations give a greater percentage of their wealth to charitable organizations than men, more often than not, outlive their spouse and assume sole responsibility for the family’s wealth. Additionally, unlike their male counterparts, women donors are much more likely to make their own philanthropic decisions without the assistance of financial/wealth advisor.

How women give—their approach, strategy, and range of giving—has been more on the very forefront of the cultural conversation around philanthropy, thanks in part to monumental gifts made by female philanthropists such as MacKenzie Scott. With Scott’s pioneering gifts, and others like them, the world of philanthropy, which has traditionally been seen as a male-dominated sphere, seems to have shifted its focus on the women who are influencing and expanding the scope of philanthropy. Or is it that world is only now paying attention?

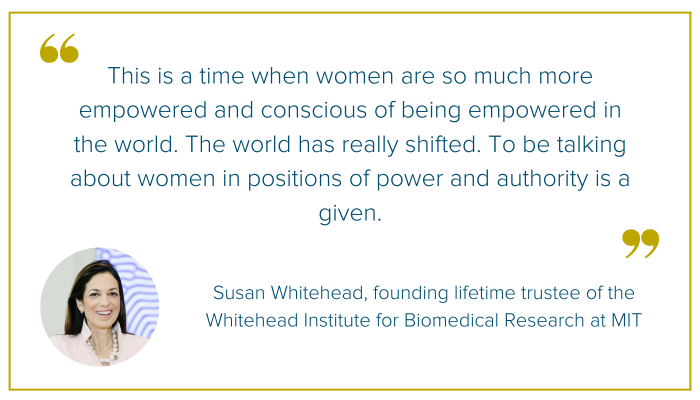

As Susan Whitehead, a founding lifetime trustee of the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research at MIT, and a member of the boards of the Museum of Science in Boston, and Horizons for Homeless Children, points out, women have always been at the forefront of change, but their roles have significantly shifted over the past few decades, and past thirty years, in particular. Women, who were once seen as the philanthropic extensions of their husbands, are now carving their path as influential donors in their own rite. As Whitehead notes, “This is a time when women are so much more empowered and conscious of being empowered in the world. The world has really shifted. To be talking about women in positions of power and authority is a given.”

Giving Changes in the Past Few Years

The past several years—the COVID years—have shown a deepening of charitable commitment and an approach to how giving is administrated. Outdated expectations for who gives and what roles donors play have shifted, and continue to shift. Women are playing a larger, and more direct, role in philanthropy than ever before.

For Allison Binns, who is the head of ESG & Sustainable Investing Strategy at Angelo Gordon, and the president of the board of trustees of the Poetry Society of America, the last few years have redefined the terms of investment. “The focus on philanthropy, for me, picked up during COVID,” she says. It was at the start of the pandemic that Binns set out to raise funds to provide meals, snacks, and PPE for hospital workers in New York City after being worried that a friend, who was an ER nurse, wasn’t eating at work, or at home after her shifts. What started as a campaign to raise a few thousand dollars to provide fresh meals, turned into a campaign that raised significant funds. “It was remarkable, to me, that our healthcare system was relying on the kindness of strangers. Our fundraising made a big difference.” She also deepened her commitment to provide direct support for the arts. “I was very worried, during COVID, that support of the arts would diminish. Since then, my focus has been on arts organizations, particularly visual arts and public art. I think the arts have been thriving. I obviously wasn’t the only one who thought supporting art organizations was important. People like Michael Bloomberg and other prominent philanthropists thought the same way. And that has been really nice to see that out of the misery of the pandemic has come a resurgence in art and poetry and literature, particularly among the younger generations.”

Of the past several years, Susan Whitehead notes that “COVID gave everybody an opportunity to just reflect upon what they were doing and why. So, I wouldn’t say that my approach changed, I just got more focused during COVID.” This concentrated focus is seen at all levels, from a rise in small tangible gifts to service-oriented organizations during the pandemic, to the large-scale gifts of Scott’s portfolio. As Whitehead notes, Scott is “really contributing very significant amounts of funds to organizations that can have a profound difference in the life of that organization. It’s like concentrated investing. She’s an explorer and mines for good opportunities. It’s also kind of an approach of our time.” And that concentrated giving, led significantly by women, is carving a path into the future of philanthropy.